The Aftermath

Originally appeared in the

Originally appeared in the

Dec 01 / Jan 02 issue of

the Met Golfer

By Merrell Noden

September 11 was a gorgeous morning. The sun was shining brightly and there wasn’t a cloud in the sky. As he waited to tee off in a sectional qualifier for the U.S. Mid-Amateur Championship at Bedford Golf Club in northern Westchester, Ken Eichele was in a particularly good mood.

Eichele hates having to play slowly, so he was delighted to be in the first group off, 7:15 a.m. from Bedford’s 10th tee. And this summer he’d improved both his iron play and putting, his Handicap Index had fallen to plus 0.6, and he’d achieved his long-time goal of qualifying for the Met Open at his home course of Bethpage Black. Eichele was playing the best golf of his life.

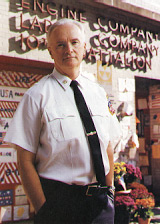

Eichele is a trim 50, though his white hair makes him look a bit older. He talks with an unblinking, no-nonsense directness that befits a Battalion Chief in the New York City Fire Department, a man who oversees 200 firemen on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. Eichele has been a fireman for 28 years, a golfer for 44, having picked up the game at the age of six by tagging along behind the older kids in his Flushing neighborhood when they’d sneak onto Kissena Park. Now that boyhood enthusiasm had become a passion. Eichele, who still lives in Queens, plays about 150 rounds of golf a year, right through the winter, when he thinks nothing of driving two hours or more to find a course that’s open.

Eichele’s first inkling that something was wrong on September 11 came moments after he’d finished nine holes. Dave Segot, a friend and a fellow New York fireman, found him to tell him a plane had hit the World Trade Center. “He didn’t know anything more than that,” Eichele recalls.

Eichele’s first inkling that something was wrong on September 11 came moments after he’d finished nine holes. Dave Segot, a friend and a fellow New York fireman, found him to tell him a plane had hit the World Trade Center. “He didn’t know anything more than that,” Eichele recalls.

As he walked from the ninth green to the first tee, Eichele asked all the people he passed if they’d heard anything more. Someone told him a plane had indeed hit the towers but that it was just a Piper Cub. “I thought, ‘Well, that’s bad, but it’s not catastrophic,’” Eichele says. “‘It’s not like there’ll be a giant disaster.’”

Eichele had played five more holes when the news turned grim: “Another friend, Pat Reilly, who plays out of Clearview and hadn’t teed off yet, he comes up to me and he’s all agitated and excited,” he recalls. “He goes, ‘The Trade Center…they flew into both of them. They’re gone.’ I said, ‘What do you mean they’re gone? They can’t be gone.’”

Eichele had been part of the rescue effort at the World Trade Center after the 1993 bombing. He saw the crater the bomb left behind. If that hadn’t brought the towers down, it was hard to imagine what could. Eichele’s first thought was to head for the city immediately, but Reilly told him all the bridges were closed.

Eichele wasn’t the only golfer at Bedford whose mind no longer was on golf. Pete Van Ingen, the 1981 MGA Player of the Year, has worked at Aon, the insurance brokerage company, for 26 years. His office was on the 100th floor of the south tower. At about 11:45 a.m., as he made the turn, he got word that something terrible had happened. “Some of the guys I was playing with were on cell phones, trying to figure out if this was real,” he says. “We played two more holes, at which point I said I have to go in.”

By this time, Eichele had finished his round. He has no recollection of turning in his scorecard, but it didn’t matter; his score was nullified when the entire day’s play was cancelled.

When Eichele and Segot found a television, Eichele knew that firefighters had been killed when the towers crumbled. “We said, ‘God! We must have lost hundreds of guys!’” he says. “‘We’ve got to try to get there.’ We thought of driving to Bridgeport and taking the ferry to Port Jeff, but figured that would take too long. We decided to try to get across a bridge, maybe by showing our Fire Department ID’s.

“The only thing I remember—my mind is really bad on that day—is a guy in the lockerroom saying to us, ‘You guys wouldn’t go in there, would you?’ I said, ‘Sure. I don’t know one fireman who would hesitate. I know we’ve got guys in there, probably hundreds of them.’”

There was a tremendous amount of activity on local golf courses that morning, some informal, some organized. The Met PGA  Championship was being held at Inwood Country Club, just south of Kennedy Airport. Inwood is about 15 miles from the southern tip of Manhattan, but the day was so clear and bright that the towers seemed to loom right up and out of Jamaica Bay. “They were right there,” says Deepdale professional Darrell Kestner. “It was just a crystal-clear day. You could see everything in detail.”

Championship was being held at Inwood Country Club, just south of Kennedy Airport. Inwood is about 15 miles from the southern tip of Manhattan, but the day was so clear and bright that the towers seemed to loom right up and out of Jamaica Bay. “They were right there,” says Deepdale professional Darrell Kestner. “It was just a crystal-clear day. You could see everything in detail.”

Kestner teed off at 8:51 a.m. with Rick Hartmann of Atlantic and Frank Bensel of Century. “The first hole at Inwood is a little dogleg-right,” Kestner says. “When we got out to our fairway shots, Rick said, ‘Hey, it looks as if the World Trade Center is on fire.’”

Hartmann’s caddie was a city fireman named Bob Regan. He knew immediately how serious things were from the color of the smoke. “That’s going to take a long time to put out,” he told them.

As Hartmann putted on the first green, the rest stared at the towers, trying to see what was happening. “I saw the windows blow out of the second building and saw a big red fireball,” Kestner says. “The plane came in from the Jersey side, so I didn’t see it. I said, ‘My God! It looks like a bomb went off in the second building!’ One minute later, the jumbo jets at Kennedy, which you can easily see from the green, we saw them just stop, right on the runway.”

Up ahead, on the second hole, Cheryl Anderson, the 2001 Met PGA’s Women’s Player of the Year from Metropolis (the top 140 club pros, male and female, were at Inwood), had also been staring at the smoke. “And as I was hitting my second shot, the second plane flew into the building,” she recalls.

One of the caddies in Anderson’s group was C.J. Papa, sports director for Channel 55 in Long Island. Papa immediately got on his cell phone and called the station. “So we knew right away,” Anderson says. “Then one of the guys on the sixth hole came running over and said, ‘They just bombed the Pentagon!’ Soon they called us in.”

A few miles away, at Plandome Country Club on Long Island, where a women’s tournament was under way, things were especially grim. “This is such a big Wall Street club,” says club manager Lee Koons.

As the situation worsened, a club professional went out onto the course to tell the players what was happening. “You knew the ones who had husbands down there,” says Koons, “because they came flying in white as a ghost and just went home.” One of the women out on the course that morning did lose her husband; he worked for Cantor Fitzgerald, the firm that was hardest hit.

Later that afternoon, Plandome members who’d been working in the city began trickling into the club looking for solace, for company. “We fed them and gave them cocktails,” says Koons. “We actually had three guys in the first Tower, two from the 23rd floor and one from the 51st, and one of those guys came back that day, obviously shaken and kind of looking for a little support, just telling his story.”

Eichele, meanwhile, was fighting traffic. Luckily, the Throgs Neck Bridge was open. He dashed home, grabbed several changes of clothing, and called his family. He was relieved to learn from one of his sisters that both his brothers were safe. They’re New York City firefighters, too.

Even his Department ID couldn’t get him over the Triborough Bridge, where the Manhattan-bound lanes were barricaded by sanitation trucks. Eichele sped off the Triborough and into the Bronx, then headed west to the Willis Avenue Bridge, driving up and over sidewalks where necessary. People were streaming across the bridge from Manhattan on foot. At first Eichele was turned away, but after pleading to see a captain, he was allowed through and raced down to his station house on East 85th Street.

Eichele had to stay uptown, but at 11 p.m. he went down to Ground Zero. “As bad as it looked on television, it was many times worse,” he says. “Glass was just pulverized. That was one of the weirdest things I saw. Blocks away, you’d see glass that had been blown out of buildings that were far away. But at Ground Zero we didn’t find one piece of glass. It was just pulverized.”

Eichele also listened to the story told by a captain working out of his station house. The captain had been standing with a fellow fireman close to the south tower when it collapsed. “He said the force of the wind was greater than a hurricane,” says Eichele. “It lifted them both right off their feet and threw them. He [the captain] grabbed on to a street sign. Our other fellow blew right by him like a rocket. That fellow was killed.”

For the next 15 hours, right through the night and into the next afternoon, Eichele helped dig through the rubble. They found no one. “Just about all the people who were found alive were out of there by the time I arrived at 11,” Eichele says. “They found a woman at 3:00 the next afternoon. I think she was the last person found alive. I didn’t find her, but I was right there.”

Of the 12 men who had rushed to the Trade Center from Eichele’s firehouse, nine were killed. Two, it seems, were carrying someone down in a wheelchair when the tower collapsed. Eichele has no doubt that he too would be dead now had he not been up at Bedford that morning. “I live in the city limits,” he says. “I don’t think there’s any doubt I would have gotten in there before they collapsed.”

Van Ingen is sure he, too, would be dead but for the Mid-Amateur qualifier. Aon lost 176 of its 1,200 employees, and his office was right above where the second plane hit. “Golf has always been my salvation,” he says. “As I’ve said to friends, golf made my life and now it has saved my life.”

The number of casualties fell with time, as victims who had been reported missing were identified and the true numbers were sorted out. By early November, the number of deaths in the World Trade Center itself stood at 2,730, as opposed to the more than 5,000 originally feared dead.

Among them, of course, were many golfers. Calls by the MGA to area clubs found a total of 68 members missing, but that’s almost certainly low and doesn’t include the many golfers who play at daily-fee and municipal facilities. As late as mid-October rumors were still swirling that a few clubs had suffered staggering losses—Canoe Brook in New Jersey and Plandome each were said at one point to have lost more than 20—but that turned out be untrue. Plandome, Garden City Golf, and Westchester were hardest hit, each losing five members, with Ridgewood, in New Jersey, and Southward Ho, on Long Island, each losing four. In all, at least 32 clubs lost at least one member.

Among them, of course, were many golfers. Calls by the MGA to area clubs found a total of 68 members missing, but that’s almost certainly low and doesn’t include the many golfers who play at daily-fee and municipal facilities. As late as mid-October rumors were still swirling that a few clubs had suffered staggering losses—Canoe Brook in New Jersey and Plandome each were said at one point to have lost more than 20—but that turned out be untrue. Plandome, Garden City Golf, and Westchester were hardest hit, each losing five members, with Ridgewood, in New Jersey, and Southward Ho, on Long Island, each losing four. In all, at least 32 clubs lost at least one member.

But, of course, these numbers don’t tell the whole story. Many club members also lost sons and daughters—many of whom had just started careers and families—or relatives and friends.

“Clubs up here were hurt badly,” says Mark Mulvoy, former managing editor of Sports Illustrated and a long-time member of The Apawamis Club in Westchester County. “There have been so many masses. At the Resurrection Church in Rye, 1,400 people attended funerals in one day, at 10, 12 and 2 p.m.”

Scarsdale lost one member, who did not work in the World Trade Center but had the misfortune to be addressing a breakfast meeting at Windows on the World, the restaurant on the 107th floor of One WTC, the north tower. Like many clubs, Scarsdale considers itself lucky that its losses weren’t worse. “A substantial portion of our membership works in the financial district, lawyers and financial people,” says Scarsdale President Mike Vaughan. “I was terrified of what we might have suffered.”

The numbers become even more awful when you learn more about the those who perished. Chris Quackenbush, 44, of Manhasset, who worked for Sandler O’Neill in One WTC, was a popular member at Deepdale—and not just with his fellow members. “We’ve named the caddie tournament after him,” says Kestner, “because he was so great with them.”

Ward Haynes, a former picture researcher for Sports Illustrated (and an old acquaintance of this writer), had begun working for Cantor Fitzgerald just one month before the attack. A member of Apawamis, Haynes had grown up in a house bordering the course. His father had been a Vietnam War hero and his grandfather Thomas Burke was MGA President in 1972-73.

“Every time Ward reached the sixth green, he’d run to his grandmother’s house, which was right behind it, and get everybody Cokes,” says Mulvoy, a close family friend. “Ward grew up at Apawamis. He was a true son of this course.”

Somerset Hills, in New Jersey, lost one member—its president. John Hartz worked with Fiduciary Trust, which occupied offices on five of the top floors of Two WTC, the south tower.

Frankie Bonomo, a firefighter from Long Island, had been part of a five-man team from the Port Jefferson CC that had made the national finals of the Oldsmobile Scramble in Orlando, Florida. Like many of us, Bonomo enjoyed golf though it can’t be said he ever mastered it. “Let’s say his love for the game was serious,” Port Jeff’s pro John Kim says smiling. “He had a very unique swing. He would loop it, then look at me and say, ‘What did I do there?’ and I’d say, ‘Well, Frank, you looped it again.’”

Bonomo was a member of the Engine Company 230 out of Brooklyn, one of the first units on the scene. His teammates were not sure they wanted to play the Oldsmobile without him, but eventually did, at the urging of Bonomo’s widow and family. With his place taken by Jerry Spiliotis, father of Steve Spiliotis, Port Jeff’s manager and a childhood friend who had gotten Bonomo into the game, they flew to Florida with team shirts on which they had printed Bonomo’s name, the number of his fire company, the date, and the words “IN OUR MEMORIES.”

In Orlando, the group found itself the focus of media attention. They played well enough, just missing the cut for the final round of competition. Still, Oldsmobile created a special fund, raising almost $10,000 in Bonomo’s name.

Although not many know it, the New York city firefighters have their own club, called Highrise. Miraculously, its handicap chairman, Battalion Chief Brian Flaherty, survived both tower collapses, but three others were not so fortunate. Two were former members, Kevin Bracken of Engine 40, 9th Battalion and Dave Wooley of Ladder 4, 9th Battalion. The third was a popular member named Mike Lynch.

In a letter to Tom Dunnam, the MGA’s manager for Course Rating & Handicapping, Highrise President Ed Gaulrapp conveyed what Lynch meant to the club. “Mike was not as active as he would have liked to be because he had a lot on his plate,” Gaulrapp wrote. “He was married with two boys, one three years old, and one just seven months. He was also studying very hard for the upcoming Lieutenant’s promotion exam. He was active in spirit, though, and I talked to him often. Every time I’d see him and ask when he was going to play with us, he would always say ‘Next week. I have to study and baby-sit this week.’

“Well, next week will never come for Mike. He was assigned to Ladder 4 in midtown Manhattan, “The Pride of Midtown.” We lost Mike along with our entire Battalion on Sept. 11. Mike died a hero doing the right thing for our city, and civilians.

“So, as president of our club, I would like to declare to you our club member Mike Lynch, Ladder 4, FDNY, as our club champion for the year 2001.”

In the balmy, indian summer days that followed September 11, the golf community rallied generously, from the simple act of replacing flags on greens with Stars and Stripes, to much larger fundraisers. “It’s been incredible how eager people are to contribute,” says John Woodeshick, the regional manager for American Golf Corporation, which has been soliciting contributions at all the city courses it operates—six in New York City and three just outside it. AGC also plans to hold fundraisers next April at each of its city courses and at a dinner in the Staten Island Armory.

There were further examples all over the Met Area. More than 700 people attended “Taste of Relief,” a gala wine and food tasting at Westchester Country Club. The fundraiser included a live and silent auction, of more than 200 donated items, which netted approximately $200,000. It was staged with the assistance of the Metropolitan Club Managers’ Association, local restaurant chefs, and people from the hospitality industry. Everything was donated.

A memorial dinner at Middle Bay Country Club on Long Island raised $60,000, and a dinner at Ridgewood Country Club in New Jersey raised $35,000. Cedar Hill Country Club in New Jersey changed the name of its Men’s Closing Day Tournament to the Day of Remembrance Tournament and raised $24,000. Other events at the club doubled that. Cedar Hill also has offered to host an outing for police, fire and EMS workers.

Meanwhile, Bethpage raised $16,500 by selling tee times on the Black course for $150. Rolling Hills, in Wilton, Connecticut, raised $26,000 with a charity tournament. The Woodcrest Club on Long Island simply solicited donations and immediately raised $7,000.

Amberview, a Connecticut club without real estate, is planning to hold a fundraiser called “The Great Ball Drop” next June. Thousands of balls (donated by Spalding) will be dropped from a helicopter (donated by Sikorsky) onto a green. Each ball “costs” $20 and closest to the pin will win its purchaser a trip for two to Pebble Beach.

The local club managers’ associations and PGA sections have made generous donations and encouraged individual members to send their own checks. The staffs at Nassau Country Club and Southward Ho, both on Long Island, asked that the money normally spent on their holiday parties be donated. The caddies at the North Shore Country Club on Long Island donated $20 per loop from an entire weekend’s rounds and raised $720.

Just to the south, ultra-exclusive Pine Valley raised funds by selling off a day’s worth of tee times. The first 100 sold out in 20 minutes. Soon the club added a second day. On consecutive Mondays 260 golfers, some from as far away as Minnesota, paid $1,000 apiece to play the top-ranked course in the world. “To my knowledge,” says Charlie Roudenbush, Pine Valley’s pro and manager, “Pine Valley has never done something like this before. But it’s such an extreme situation. Nothing’s the same anymore, is it?”

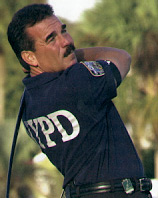

At the PGA Tour’s National Car Rental Classic in Florida in mid-October, a pro-am spot was given to Patrick Marcune, a 22-year veteran of the New York Police Department who had been at Ground Zero since the day of the attacks. The 44-year-old Brooklynite was invited after New York stockbroker Gene Singer canceled and suggested his spot go to a police officer he knew who happened to love golf. Marcune and his caddie Bob Hoops, also a police officer, played while wearing navy blue shirts with the NYPD seal on their chests and sleeves and the bold letters on their backs. Marcune, who works at the 68th Precinct in Brooklyn, didn’t feel comfortable accepting the pro-am berth at first, but his wife sensed his growing depression and insisted that he take the spot. “You can only look at something like that for so long,” Marcune said. “She said, ‘You better go.’”

At the PGA Tour’s National Car Rental Classic in Florida in mid-October, a pro-am spot was given to Patrick Marcune, a 22-year veteran of the New York Police Department who had been at Ground Zero since the day of the attacks. The 44-year-old Brooklynite was invited after New York stockbroker Gene Singer canceled and suggested his spot go to a police officer he knew who happened to love golf. Marcune and his caddie Bob Hoops, also a police officer, played while wearing navy blue shirts with the NYPD seal on their chests and sleeves and the bold letters on their backs. Marcune, who works at the 68th Precinct in Brooklyn, didn’t feel comfortable accepting the pro-am berth at first, but his wife sensed his growing depression and insisted that he take the spot. “You can only look at something like that for so long,” Marcune said. “She said, ‘You better go.’”

Orange Hill Golf Club, a public track, just west of New Haven, Connecticut, asked Eichele if four men in his command would like to be brought up by limousine for a fundraiser, at the end of which they’d be presented with a check. “It was the first thing these guys had done for a month, outside of searching down at the Trade Center,” Eichele says. “They had a good time and the people were great.”

On the eve of the U.S. Mid-Amateur Championship in California, defending champion Greg Puga, as is the tradition, spoke at a dinner for all the golfers in the field. In addition to telling of his appearance in The Masters and his practice round at Augusta National with Arnold Palmer, Puga spoke of playing in the USGA Men’s State Team Championship in the same group as Peter Meurer, a retired firefighter from Staten Island.

“Peter said he was honored to be playing with me,” Puga said. “But I was the one who was honored to be playing with him. I was in the presence of greatness, of someone who helped people every day and who saved lives. God bless people like Peter and all the firefighters around the world. God bless America.”

The terrible echoes of September 11 reverberate still, but gradually clubs are beginning the difficult process of recovery. Westchester Country Club, like others, draped American flags over the lockers of those that perished. And, like others, it extended special privileges to the victims’ wives and families. Plandome did essentially the same. “They’re free of dues assessments and minimums,” Koons says. Plandome also changed the name of its October scramble to the Memorial Tournament, and plans to honor future winners with a plaque in the locker room. Garden City Golf plans to place a memorial plaque in its locker room just like those honoring its losses in past wars. And during the national candlelight vigil President George W. Bush called for on September 14 the members and staff of Scarsdale Country Club stood together in silence, holding candles.

At Metropolis, Cheryl Anderson says people see their lessons as a departure from the awful, unimaginable status quo. “Most are so happy to take their lessons because it’s a nice break for them,” she says. “But it’s a completely different atmosphere now.”

The message at Van Ingen’s former office number instructs callers to reach him by cell phone and he must correct himself when he says he “worked” for Aon, because he still does. He didn’t feel like playing the rescheduled Mid Amateur qualifier, but has begun playing again. “I’m trying to get back to normalcy, as best I can,” he says.

Several weeks after the attacks, a textbook on chemical and biological warfare sits on Ken Eichele’s kitchen counter. He points to a steroid inhaler next to it. “I use that every day,” he says. “We all developed coughs, sore throats. When you got home and opened your mouth to brush your teeth, you could see your tonsils were white, from fiberglass and crushed glass.”

Eichele worries about the men under his command, and the widows of the men in his command, at least one of whom still hopes that her husband will walk through the door. Counselors have urged firemen to make sure they grieve for themselves and their lost brothers.

“They’ve told us to shut it all off at some point: ‘Close the door and grieve for yourselves,’” Eichele says. “The public is using the firefighters to do their grieving. And that’s okay, but at some point we have to grieve for ourselves.”

Eichele says he finds himself crying sometimes when he’s alone in his car and sees the faces of guys he’s known for 25 or 30 years. He points out that one good thing to have come from the events of September 11 is that the public has a better understanding of what firefighters do and the risks they run.

Eichele couldn’t make the rescheduled Mid-Amateur qualifier because he was working at Ground Zero, but the USGA, alerted by the MGA, promptly awarded him a berth in next year’s final field at the Stanwich Club in Greenwich, Connecticut. It’s a gesture for which he’s grateful, but which makes him a bit uncomfortable.

Eichele played golf twice in the weeks following the attacks, turning a lifelong love into an act of quiet defiance. “For a while I didn’t want to play and didn’t have time to even if I had wanted to,” he says. “But I believe that if you let the terrorists take away your liberties, then they’ve won.

“I love golf and hope to play a round of golf on the day I die. But the bottom line is that it’s just a game and that has to be kept in perspective. So if golf is something you’ve always loved to do, then you should do it now.”